(This story of Kirsten’s was published in the Travelers’ Tales series of books The Best Women’s Travel Writing volume 9)

Chasing Tornadoes: “The Suck Zone. It’s the point basically when the twister… sucks you up.”—Dusty from Twister

BY KIRSTEN KOZA

“Go, go, go!” Ron bellowed. He must have sensed my hesitation.

Was I supposed to pull a one-eighty and drive away from the tornado or actually haul ass through a Nebraskan cornfield toward it? Then the twister flickered and was gone.

“It’s coming back,” Ron yelled. “It’s going to come down on the track right in front of us!” And then it did. A full vortex. “GO! Towards it!”

I stomped on the accelerator pedal of the intercept vehicle, a hail-dented little Pontiac Vibe. We were doing eighty in a cornfield. Getting stuck was not an option.

The Star-Trek sounding computer-voice on Ron’s laptop said, “Warning. You are approaching severe weather.”

The Star-Trek sounding computer-voice on Ron’s laptop said, “Warning. You are approaching severe weather.”

We were approaching my first tornado, now just 500 feet in front of me. The dark, jagged cord of wind looked like it could loop and lasso me from my seat. Now 200 feet. I thought about the tornado in the Wizard of Oz—it was made by spinning a black sock. It was ingenious and inexpensive. I was living a movie, a nightmare, and a dream come true. My heart pounded in my temples. This was real.

“Gone.” Ron slammed his laptop shut. “There was another one there on the hill as well. So what did you think?”

I whooped my reply cowgirl-style. It was time for a bar, drinks, dancing, screaming, bloody steaks, mashed potatoes, do the twist.

It was the last day of the storm chase, and I’d driven 12,365.3 miles through the summer while Ron Gravelle, storm predictor, forecaster, and certified chaser, navigated us to the best storms across the United States. The weather had been a storm chaser’s worst nightmare, sunny and dry. Yet Ron overlaid hundreds of weather maps and found a variety of extreme conditions: killer fork lightning in Louisiana, an isolated cell in New Mexico with a cactus and canyon backdrop, a Kansas storm that looked like it could plough a house across a field, a front in Colorado that resembled an alien ship from Independence Day. I’d finally seen my first tornado. But not my last.

It was the last day of the storm chase, and I’d driven 12,365.3 miles through the summer while Ron Gravelle, storm predictor, forecaster, and certified chaser, navigated us to the best storms across the United States. The weather had been a storm chaser’s worst nightmare, sunny and dry. Yet Ron overlaid hundreds of weather maps and found a variety of extreme conditions: killer fork lightning in Louisiana, an isolated cell in New Mexico with a cactus and canyon backdrop, a Kansas storm that looked like it could plough a house across a field, a front in Colorado that resembled an alien ship from Independence Day. I’d finally seen my first tornado. But not my last.

“So, you heard what happened with Ben and the thirty thousand dollars at the border?” Len, the South African stock car racer, asked me when we picked up the SUVs at Will Roger’s Airport in Oklahoma City.

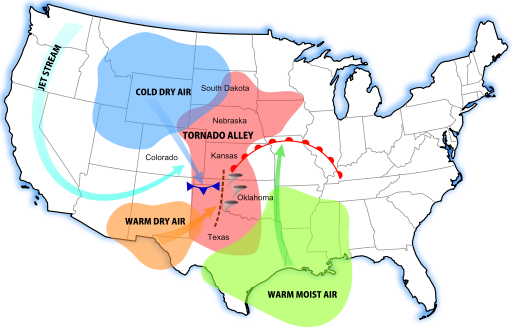

It was four years since my first chase, when I had—upon whim—begged Ron to take me on as a driver to pursue extreme weather, one of the things that both frightened and fascinated me most on the planet. Now I was back in Tornado Alley, the expansive swath of the United States between the Rockies and Appalachians, stretching from North Dakota all the way south through Texas. I was here with Ron again—he’d been hired by a television network from Hong Kong for a ten-day storm chase and had asked me to drive for him. Ron was sporting a t-shirt that showcased a spectacular Colorado tornado, an image of his that had been published in National Geographic. I desperately wanted to take a picture like Ron’s. That was the only problem with being an intercept driver—less opportunity to shoot photos. But it was also the only way I could afford to keep doing this.

Ron handed me a set of keys to a brand-new silver Chevy Suburban, extra-long. I’d already heard the story from Ron about his brother-in-law Ben and the thirty thousand dollars. “He had loose change in his pocket,” I said, “which put you guys over your limit of ten thousand each in cash that you could bring in from Canada. But I can’t believe the border officials seized the entire thirty-grand because of a couple coins? Freaking disaster.”

Stock-Car-Len grappled me in a bumper-grinding hug. There was nothing sexual about it. “The entire trip budget, gone,” he said, shaking his head, “and all Ron has is a little slip of paper so maybe he can get it back from someplace in Canada. Those machines at the airport can see what you’re carrying.”

Later that morning we made our introductions with the Chinese celebrities and film crew in the lobby of the airport Ramada.

Keiky, the scriptwriter, shook my hand, “Nice to meet you. This is He.”

“Who?”

“He.”

He shook my hand. He was China’s George Clooney.

“And this is “Lawlaw Law.” Law had evidence of a former harelip. His job was to report on his colleagues, back to China.

It was our turn to introduce a few of the storm chase team. “This is Ben, Len, and Jen.” Nine Asian faces stared at us in disbelief.

Soon our trio of storm-chase SUVs was on the highway and heading away from Oklahoma where the weather was going to remain sunny and dry for a week. Stock-Car-Len overtook us slowly so that Ron’s cameraman, Ben, could film us. As they passed, I waved to Justin, a student from Singapore who’d signed on at the last minute and was hoping his mother would never know he spent his summer vacation chasing tornadoes instead of tail. It would be a difficult secret to keep, though, since it was a major television production and his parents were fans of Wong He. Then Stock-Car-Len sped ahead to get a shot of the lead vehicle.

I had the two Hong Kong celebrities in the backseats of the cavernous Suburban. I inhaled the glorious toxic scent of new car. Keiky, the researcher and scriptwriter, sat beside me in the passenger seat. Lawlaw Law was sawing logs already from the back row.

“Nice leather,” Wong He said, admiring the Suburban. He was a Buddhist. Leather seemed an odd thing for a Buddhist to admire.

Yan Ng, the female star, put on a coat even though it was almost a hundred degrees outside. I examined her prettiness in my rearview mirror. According to Justin, she wasn’t just a TV presenter but was also a famous singer.

“Where are we going?” Keiky asked me excitedly.

“To The Big Texan, in Amarillo, Texas, to eat rattlesnake, bull testicles and a free seventy-two-ounce steak—free, that is, if you can eat the whole thing in an hour,” I drawled, and then felt like an idiot for drawling. “Have you been doing a lot of research about storms?” I asked her. I wasn’t sure what I should explain. As the scriptwriter, she really should have been riding in the lead vehicle with Ron.

“Have you seen a tornado before?” she asked.

“Yes, with Ron, in Nebraska. I drove right toward it.”

“Was it an F4 or F5?” Keiky was schoolgirl cute, adorned in kittens and bows, but I had the sneaking suspicion she could be as deadly as a crouching tiger.

“A tornado only gets an F-rating if it hits something like a barn, bridge, outhouse, or Wal-Mart, and then the damage is assessed,” I explained. “The tornado I saw didn’t hit anything, so it wouldn’t even be counted. Even if we drive toward a tornado that’s a whopping F5 in power and size, it’s a zero if it doesn’t hit something. Practically every year you hear it’s a record-breaking year for tornadoes, right…yes?”

Keiky nodded—but she might have been nodding off to sleep.

“It isn’t that there are more tornadoes. There are just more housing developments and shopping centers being built in their paths,” I continued, trying to make my voice more animated, like a teacher during story time. “More twisters are being counted with F-ratings because there are simply more objects for them to hit.”

“Uh-huh,” Keiky said, rooting through her enormous purse—probably looking for a pair of earplugs.

“Anyway, we’re not going to get any severe weather for a few days—it’s been really hot and dry. And we’re going to have to head far north for the weather coming over the Rocky Mountains. There’s been a drought in the U.S. all summer. For a big storm you need a few main ingredients—moisture for starts, and there hasn’t been any, instability, and lifting agents…” I saw Keiky’s eyes glaze.

Ron explained it so well. He used ice fishing as an analogy. I decided to channel him. “Hunting for tornadoes is like going on an ice-fishing trip,” I said. “You aren’t going to try and drill a hole through ice that’s 1,000 feet thick—you’re going to look for where it’s thin. If the ice is thin, it’s easier to break, and then you get a hole. It’s when the weather conditions such as updrafts, lift, moisture, and instability can penetrate the CAP, where the hole is, that you can get a tornado. Ron will be looking for where the ice is thin.” I loved this so much. It turned my crank, but something about my explanation wasn’t working. Did they even go ice fishing in China?

“Have you seen the movie, Twister?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” Keiky applauded. “We watched this for research.”

“It’s just like Twister,” I said. “But I’ve never seen flying cows.”

“How long until we will be in Texas?” Keiky asked.

“Just a couple hours.”

She sat back and closed her eyes. Lawlaw was snoring, and Wong He and Yan were hunched over their phones.

A few hours later, while the Hong Kong film crew ran around the leaning water tower of Texas, the storm chasers watched a single cell storm, in the middle of a horizon-to-horizon blue sky, making its way across the plains.

Ron nudged me. “I told you.” He pointed north. “We’re heading to Colorado and Nebraska, then over to the Dakotas. We should get something big in the Dakotas.”

Wong He saw me taking pictures of the little storm. “What?” He asked.

“It’s exactly what we need. It’s a great sign. It means there’s now moisture.” I was thrilled.

“It’s just some rain. Pffft,” he said, dismissing it with his hand. “It’s not a tornado.”

It hit me: No wonder Ron’s brilliant ice-fishing analogy seemed to fall on deaf ears. The TV crew was here to see a tornado—they weren’t interested in the process. And because of that, unless they saw a tornado, the trip would be a write-off. The work that went into finding a tornado was part of the journey. But the Chinese group was snacking and snoozing and gaming, Facebooking and tweeting and texting. They were more involved in their virtual lives than with what was happening in the here and now. They’d seen Twister.

Day two: Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, all in one day’s drive, and now on our third day we were back in Nebraska and the weather was severe. I kept my eyes on Jen’s taillights while also watching for deer or livestock that might fly across the road. Wind rocked the Suburban, and my passengers sounded like spectators at a fireworks show as they oohed and ahhed over the forks of lightning. Nobody was hunched over a handheld device now; their faces were pressed to the windows. I angled my rearview mirror back at the road. Stock-Car was right behind me, but not too close. The man could kiss your license plate on a highway. I recognized this roller coaster of road—we were near Valentine.

Lightning eviscerated the sky.

“There’s rotation!” Ron yelled over the thunder from behind.

I stood under the power lines between Wong He and Justin. Sand fleas attacked my shins, but I didn’t move. The Chinese cameraman, soundman, and tech all struggled with their wires and equipment while I took photos. Bright yellow grass angled in the wind against an ash blue sky. Then, out of the revolving super cell above us, a funnel descended. I was transfixed. It was right over us. Hell from the heavens was reaching for me. In order to be a proper tornado, it would have to come in contact with the ground. I prayed it would.

My first tornado had looked like barbed wire, but this funnel was smooth—almost sexual. I looked behind me and clocked where the Suburban was, to calculate when I’d need to run. Maybe now was the time to run. Was now the time to run? Ron, Ben, and Jen, whose long blonde hair whipped up over her head like a science experiment, were on the road beside the vehicles. Why was I standing on a hill under the power lines with a tornado trying to materialize above me? In Twister, the character Dusty warned that one should stay out of the suck zone. And if this cone reached the ground, we’d be right in it.

“We’re going east!” Ron yelled.

We bolted to the vehicles and headed down the road alongside the storm. Then the rain hit. We had been ahead of the front. Now we were behind it, and it was like driving through a waterfall. I masked my slight state of panic with my “business as usual” face. Storm chasing becomes dangerous when you can’t see. This was now officially death defying, and just like the time I was on an airplane with malfunctioning landing gear, my son Rigel, now thirteen, popped into my head.

I didn’t want to die and be Rigel’s big disappointment and life-long baggage. Regardless, I was still annoyed by my mother’s gym acquaintances They thought it was so cool that I was tornado chasing until they found out from my mother that I also was a mother, and then they disapproved. I white-knuckled the steering wheel as we hydroplaned. You don’t have to stop living life to the fullest just because you’ve given birth. Rigel was proud of my quests.

We turned onto a gravel road.

“You’re going to get to try out your helmets,” I shouted. “We might get hail.” I grinned at Wong He and Yan. They’d brought helmets from China.

Wong He smacked the top of his helmet to prove its strength, and then before I knew it he was out of the Suburban and leaping across the grasslands, talking to his video camera in the torrential downpour and deadly lightning while the crew set up.

Lawlaw Law made a sarcastic comment in Chinese. Tone of voice can be universal.

I videoed He as he jogged to the lead vehicle to stand under the shelter of the rear door with the crew. Suddenly Woody, whose job was a mystery to me, pushed Wong He and grabbed his camera, then tossed it into the back of the SUV. There was rapid-fire shouting in Cantonese. When Woody turned his head—maybe he felt me watching—Wong He lunged for his camera and marched back to our Suburban with it.

I wanted to ask what had happened, but Lawlaw Law was sitting in the back with folded arms and an expression of extreme distaste on his face. What I saw in the rearview mirror frightened me more than an unseen tornado. I saw primal loathing, maybe even utter hatred. I fiddled with the skipping rope that Ben had bought me in Colorado so I’d have something to jump over at rest breaks. (For the first few days I’d been air-skipping in parking lots across five states—you had to do something to counteract the fast food diet, arguably the most dangerous part of tornado chasing.) I looked back in the rearview mirror. Wong He was peeling off his sopping clothes. He was gorgeous. He was living on apple slices and water.

I, on the other hand, was living on Quarter Pounders. I was hooked. It happened every time I did this. Maybe I was partly doing this as an excuse to eat salty, greasy, splendid junk? I angled the mirror at myself. Yuck, I thought. You really are what you eat. I turned the mirror back to He. It was perfectly fine to admire the guy—even if I was married. Surely it was acceptable to admire the George Clooneys on our planet. I grabbed my pulled pork sandwich out of the center console and took a huge bite. Fat ran down my chin. Oh, God, I thought, I love this job.

Nebraska, and then just one day later, Iowa and Missouri, and the following morning Minneapolis, Minnesota—where Stock-Car was rear-ended during morning rush hour traffic. The SUV was fine, but the car that hit Len, Ben, and Justin was totaled. Len figured the young driver must have been texting to miss the large SUV right in front of him.

Day six, South Dakota—the Chinese group were still texting and tweeting and Facebooking; in restaurants and on the road, they never stopped looking at their handheld devices. Day seven, North Dakota—Ron filed official weather reports over his radio. A road sign for Winnipeg, a sign for Fargo, and many wood chipper jokes amongst the westerners later, we were now parked on a dirt road as dust sandblasted anyone who dared to stand outside. A super cell worth risking my camera lenses for was fast approaching. I could barely see due to the flying dirt, but I recorded Yan being blown right off her feet. The soundman’s plastic raincoat flapped loudly as it was shredded by the wind. The ingredients were almost perfect for a tornado.

“If a tornado is going to come down, it’s coming down right there!” Ron stood with his hands on his hips, apparently oblivious to the stones hitting his bald head. He did the same thing in hail. He was so intent on the weather I doubted he’d notice flying monkeys. I was terrified of the flying monkeys.

A whirlwind of grit scoured my eyeballs, and I ducked inside the Suburban to retrieve my sunglasses. Today I was driving for Ron in the lead vehicle. Wong He was sitting in the back of the 4×4 on his own. Now was my chance to ask.

“He, what’s going on? Everyone seems mad at you. They’re obviously ignoring you. It’s practically a Mennonite-style shunning.”

“You noticed?” He threw his hands up in exasperation. “They want me to lie and say I saw a tornado, when I haven’t. They’re all mad at me because I won’t do it. I was hired for my integrity, for my reputation. I’m not going to ruin my reputation.”

“The trip isn’t over. You could still get a tornado. Maybe any minute…” I hoped we would, but this storm was so spectacular, it didn’t matter if we didn’t.

“You know what Yan’s line in the script was, just then, when she was blown over? Her line was, ‘It’s windy.’ That’s the type of lines they’re giving us. That’s like filming someone eating chicken and they say, ‘It tastes like chicken.’ They’re giving me nothing. They don’t care about the storms or how they’re made. They just want to see a tornado.” He picked up his camera. “Did you see them take my camera yesterday? They told me I wasn’t to film anything myself because they’re paying for me to be here. I took my camera back.”

“I saw that. It was terrible.”

“I feel sorry for them too, though,” he said. “There’s so much pressure. They have to film a tornado. They can’t go back to China without one—it will be seen as their failure. That’s why they want me to lie. I talked to the executive producer in China today. He said I should just say on camera that I saw one, and he won’t use it in the show, but that way I can at least get along with the crew.”

I had a bad feeling about that. But I said nothing. I put on my sunglasses and dusted off my lens before stepping back outside.

Ron was looking at his camera’s viewer. Then he lowered it and squinted at the field, now just a wall of debris heading right at us.

“GO!!!” Ron ran full-speed toward the SUV with me right behind him.

I jumped into the driver’s seat, heard doors slamming behind me, and floored it, spitting up stones. I looked in my mirror. Jen was screaming at the Chinese crew to get in the vehicle. You didn’t have to be an expert lip reader to see she was tossing F-bombs at them through the dust.

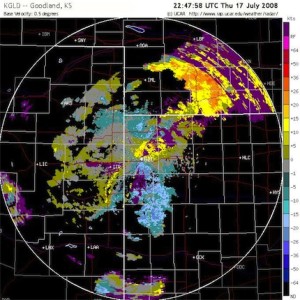

“Jen isn’t following yet,” I said to Ron, who was looking at Baron Mobile Threat Net, his live weather software that showed our vehicle in relation to the storm. We crested a hill and were airborne, then sped down the far side.

“Take the next left,” Ron ordered.

We were at the next left. I hit the brakes. “They’re still not here!” They wouldn’t know if we went straight or left. I didn’t have my walkie-talkie. It was in the other truck. Where was Jen? I purposely held back and watched the top of the hill.

“GO!” Ron commanded.

I saw Jen crest the hill. I hit the gas and braked and attempted to drift around the corner on the loose gravel, but the vehicle’s excellent traction control made it difficult.

“My camera picked up a tornado but we couldn’t see it,” Ron said. “It was behind the debris. It was right there. Exactly where I said it would be.” Ron tilted his camera so I could see, but I didn’t want to take my eyes off the road.

Ron liked my driving because he said it was “smooth.” I could pass traffic on the shoulder of the fast lane doing one hundred miles an hour while he calmly worked the weather.

Just then, a blinding ball of light exploded behind me. Stock-Car’s SUV had been hit by lightning. But they were still coming. Now that man could really drive. Hail pummeled the windscreen; I was driving sightless and knew it was wrong, but I didn’t want Ron to see me fail. And I didn’t want the TV crew to miss a tornado because of me. The barrage of ice stones on the roof was deafening. I kept driving. Ron told me to take the next right. I missed it. He gave me the “special” look, the “how especially stupid are you” look—the one he saved for dimwitted hotel receptionists and waitresses.

That evening as we checked into our hotel, Jen and I made excuses to Ron, Ben and Len about needing vitamins and not a germ-loaded buffet, but in truth we’d already spied the buzzing neon signs of a Mexican restaurant close to our hotel. We got drunk on Oz-green margaritas—which we decided had lots of vitamin C—and fended off a grifter in a Hugo Boss suit and a clip-on tie. We tumbled into our beds hours before the buffet-seeking storm chasers and Chinese crew were tucked into theirs.

Day eight was the other kind of “suck zone.” It had been a fruitless trek back and forth between the Dakotas. And now, on day nine, we had to drive 900 miles back to Oklahoma. The trip was over. For the Canadian crew, it was a success. We were chasing storms. For the Chinese crew it was a failure. They were chasing tornadoes.

There was a camera attached to my side-view mirror that was focused on me (or maybe my crop of fast-food pimples), and another on the front of my vehicle, plus one on the passenger mirror trained on Wong He. We both wore microphones. The cameraman and soundman were squished between us, capturing our road-trip banter. We talked about Facebook etiquette and the chiropractic back cracking He had given me the day before. But I desperately wanted to ask him whether he’d lied about seeing the tornado. Jen had told me as we loaded the trucks in the morning that both the director and Keiky had asked Ron if they could buy footage of past tornadoes he’d captured, but they didn’t give him the reason. You couldn’t just lie about a tornado. I knew Ron would never sell it to them if he thought they were going to lie. But I couldn’t ask He about this while on camera.

I was relieved to see Wong He back in the passenger seat. He’d driven for a stretch earlier in the day—he wanted to drive, he said, to help me out, because I was exhausted. He’d said it was his gift to me. Then he overtook a truck on a blind hill, which was the closest any of us had come to dying on this trip.

“Stock-Car-Len sure tore a strip off your hide for your driving earlier today,” I said.

The cameraman leapt in for a close-up of my face. I hadn’t known the man spoke English until that moment.

If I had a crystal ball, like the Wicked Witch of the West, I’d have learned that nine months later the Chinese crew’s disappointment over not filming a tornado would be nothing compared to Ron’s frustration over never reclaiming from U.S. customs the thirty thousand dollars he’d ponied up to fund the trip. And that the storm chasing episode had yet to air in Hong Kong due to a bureaucratic quagmire—so I still wouldn’t know if Wong He had to lie or if he’d told the truth.

But for now, I ignored the cameraman. Keeping my hands on the wheel, my eyes on the road, and my mouth shut, I drove on.