By Kirsten Koza, author of Lost in Moscow

[This article originally appeared in OUTPOST: Travel for Real magazine.] Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear. Crap. Right out of Jurassic Park. It’s Disco Night on Easter Island and a panting Chilean sailor’s reptile-face is filling the passenger mirror of my new Irish pal’s rental jeep. The Easter Island Foundation recommends that women shouldn’t walk home from the Disco alone. As I slam the locks shut and scream with laughter at Gerry that she must go faster, I’m thankful I left my mountain bike at Petero Atamu, a $15 per night “residencial” hotel, atop the steep, rocky, rutted, dirt road, exiting downtown Hanga Roa, the only town on the island of Rapa Nui.

Objects in the mirror are closer than they appear. Crap. Right out of Jurassic Park. It’s Disco Night on Easter Island and a panting Chilean sailor’s reptile-face is filling the passenger mirror of my new Irish pal’s rental jeep. The Easter Island Foundation recommends that women shouldn’t walk home from the Disco alone. As I slam the locks shut and scream with laughter at Gerry that she must go faster, I’m thankful I left my mountain bike at Petero Atamu, a $15 per night “residencial” hotel, atop the steep, rocky, rutted, dirt road, exiting downtown Hanga Roa, the only town on the island of Rapa Nui.

Hey, Lonely Planet, the natives call Easter Island “Rapa Nui” which means “Big Island” and after biking for 18 sweat-soaked-days over the 3 main volcanoes and the 70 secondary volcanoes (some as high as the major cones) I can’t help but notice that your statements that the island is “tiny” and only “117 sq km” are misleading to those not ensconced in an air conditioned tour bus. According to the island’s Museo Antropologico Padre Sebastian Englert (using the satellite image provided to them by NASA in the 1980’s) Easter Island is 173 square kilometres. But Lonely Planet’s mysteriously missing mileage is nothing compared to the multitude of inadequate maps available. Beware the Rapa Nui Guide road map. It’s only natural to have difficulty finding the 886 gigantic stone heads (the largest monolith or Moai being 160-182 metric tons) using a map whose scale is so ludicrous that they depict the 1.5-hour granny-gear slog from town to the top of Rano Kau Volcano to be a gentle 2 kilometres instead of a skyward 9.

Imagine ultra Olympics done naked. This is the Birdman Competition and its starting gate was at the top of Rano Kau Volcano. Nude luge down the volcano on a banana tree, freestyle swimming with sharks, martial arts while rock climbing, and rhythmic gymnastics all rolled into one bare butt sporting event. In the 1600’s the Birdman contest took over from the previous Moai building mania. In rebellion the islanders snacked on one another’s barbequed toes, toppled the massive stone heads they’d been building since 800 AD and the new cult of the Birdman soared by 1680. The clans built the Village of Orongo high on Rano Kau to serve as their stadium to view the event, which determined the next chief. The competitors had to race down the 1400-foot vertical cliffs (the jury’s out on that elevation as well), then plunge into the crashing surf and swim to an islet to retrieve the first Sooty Tern egg of the season. Sometimes it took days to bring back an intact egg. The winner, or in some cases the winner’s sponsor (picture some pampered rich geezer with long finger nails) was made the Birdman and island chief until someone else survived the annual championship.

I watch Mokomae draw Birdman’s image on my left ankle. I’m 40 and I’ve never had a tattoo before. I’m sweating profusely in anticipation of the needle. It cuts through my flesh like a hot scalpel. Maybe this wasn’t such a good idea. Mokomae works skillfully—entirely freehand. He’s not just the island’s tattoo artist he’s also a sculptor and a star dancer of the Kari Kari Cultural Ballet. His lean angular non-Polynesian features cry out that Thor Heyerdahl wasn’t completely out-to-lunch theorizing that the island natives didn’t all come from the Marquesas back in 400 AD. There were the “long ear” and the “short ear” tribes and the “fat people” and the “skinny people” tribes. Mokomae must have descended from the “skinny people”. With his hooked nose, he looks like the 19th C engraving of the tattooed Rapa Nui native, Tepano. I ask Mokomae if he’s Rapa Nui. “Yes,” he booms as if it was an insane question. He’s proudly loudly Rapa Nui like all the aboriginals I’ve met. No Madonna to be heard, the music blaring from the restaurants and households of the 3800 residents is rhythmic, harmonic, diaphragmatic, chest thumping, Rapa Nui. 3700 kilometres from the Chilean coast, their culture thrives in its isolation. I love this place. The same choreographed traditional storytelling dances that tour-bus-tourists pay to see Kari Kari do at their prohibitively expensive digs in Hanga Roa Hotel, is how the locals actually dance when out for a night on the town.

Myself, and my three mountain biking companions from Canada, cycle into a continuous headwind and crosswind for several hours along the rugged south east coast of the island. I glance back and see Arizona, and yet Irish Gerry who we befriended at the “residencial” was bang-on when she described Easter Island’s interior as the emerald hills of Ireland. But then the next vista is the hardened lava of Hawaii, except Easter Island’s volcanoes are extinct. Finally, Karen, Malcolm, Rigel and I reach Ahu Tongariki, the largest restored stand of Moai. In a cloud of red dust the unthinkable happens. The tour-bus-tourists arrive infiltrating our private hard earned view. Malcolm and Rigel both out of water and armed with practicality, ask the Rapa Nui bus driver and guide whether they can hitch a ride back to Hanga Roa. Malcolm offers money. The guide refuses the pesos and says, “We’re just happy you came to our island!” Karen looks disappointed that my hubris won’t allow me a bus ride and she eases her tender tush back on the bicycle seat. As we pedal we make plans to go back to the Moai in the midnight moonlight when the blue-haired tour groups are tucked in their beds.

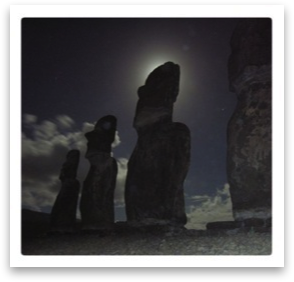

Creepy. Karen Fockler and I tiptoe by the light of the full moon towards the towering silhouettes of Ahu Tongariki. The South Pacific surf sounds like mortar fire on the high volcanic rocks behind the Moai. We’re completely alone except for the 15 Rapa Nui ancestors looming over us. We didn’t even see a car on our trip across the island. We have the feeling we’re doing something wrong or about to be caught, but we’re going to try to accomplish our task. We’re going to paint the Moai… with our bicycle lights and flashlights during a long exposure shot. The wind sprinkles us in sea spray. It’s going to be tricky. The tripod doesn’t cooperate on the stones. It’s hard to focus in the dark. We inch closer to the Moai and set up again. We sweep our flashlights over the figures, trying to evenly paint them with different hues of light. We’re too far away. We go closer, stumbling in the dark over the uneven earth. There’s a dry scuttling sound. What’s that? We illuminate the ground. Hundreds of giant cockroaches are crawling at our feet. “Freaking hell, we’re on the Ahu,” I cry-out. This time it’s Return of the Mummy. Although no longer punishable by death it’s “tapu” or taboo to climb on the Ahu, the rock covered platform beneath the Moai—the burial ground of kings. We’re walking all over the resting place for the human-bones that belong to the stone faces above. “Car!” Karen warns. We dash around extinguishing our lights. The car is nearing. I know there are no electronic sensors on the Ahu but regardless I’m plunged back to my twenties when my friend Hamish and I climbed into an exhibit at the ROM and instantaneously over the museum loudspeaker a voice threatened, “Get out of the bat cave now!” Karen and I hold our breath as the car slows. I plead internally that it isn’t a Chilean Parks Official. The car passes.

There is a Rapa Nui expression “anytime the Chilean Navy comes, it rains.” The night they arrived, the monsoon rains did too, and a male cat pissed on my sandals. There is passionate anti-Chilean sentiment on the island especially amongst the middle-aged to elderly, who remember being confined to the town of Hanga Roa by a wall covered in barbed wire, from the 1890’s to 1960’s. In 1973 a Chilean military coup left the islanders under direct military rule. A native woman at Anakena Beach sobs telling me of soldiers putting guns to the heads of children. And yet a Chilean waiter from Pea Beach Bar chases me through Hanga Roa so he can return my Nikon and three gigabytes of memory cards I’d forgotten. The younger Rapa Nui are marrying mainlanders regardless of parental scorn; even Mokomae is in love with a policewoman in the Chilean Carabineros.

In stark contrast to the negative emotion the Rapa Nui feel towards Chile, is their passionate affection for Canada. Canadians built a hospital for Hanga Roa during the mid-sixties and the islanders will never forget. I’m gambling with Margarita and her family on their dirt laneway at Petero Atamu. “Amiga,” the Rapa Nui grandma says to me and Margarita pats her heart and hugs me tightly, telling me she can never thank Canada enough. A taxi shows up, she grins and winks, “I have something for us.” She retrieves a bottle of Pisco from the cab driver. She’s had it delivered to share with me. She pours the Chilean brandy into a huge tumbler. I try it and am astonished how an 80 proof alcohol can have so little taste of alcohol. I feel the kick instantly and beam. I’m going to be losing money tonight in the coin toss game and I doubt I’ll be biking tomorrow. The warmth, generosity, and safeness of this island the Rapa Nui also dub “The Naval of The World” envelops me. Okay, the booze accentuates the warm-fuzzies but regardless, I’ve never locked my five-thousand-dollar mountain bike (don’t tell my insurance company), I’ve slept doors thrust wide open at night (with only two intruders, a sweet street-dog and a pooping chicken) and I’ve not once had that feeling that anyone wants a piece of me. For the first time ever when travelling, I don’t want to go home to Canada.