Regardless of a high risk travel advisory, Kirsten went to Kyrgyzstan for three weeks and mountain biked the Kyrgyz Republic section of the Silk Road and the rugged mountain tracks with Elena (a Kyrgyzstan/Russian guide) and drank fermented mare’s milk with Cholpon (a Kyrgyz cultural guide) which Kirsten vomited up the rest of the day while carrying her bike up Chok-Tol and then back down again in the dark.

Regardless of a high risk travel advisory, Kirsten went to Kyrgyzstan for three weeks and mountain biked the Kyrgyz Republic section of the Silk Road and the rugged mountain tracks with Elena (a Kyrgyzstan/Russian guide) and drank fermented mare’s milk with Cholpon (a Kyrgyz cultural guide) which Kirsten vomited up the rest of the day while carrying her bike up Chok-Tol and then back down again in the dark.

Sergey of Nomad’s Dream in Kyrgyzstan put together this incredible adventure of a lifetime (here is the itinerary with details and prices) and supplied a list of cultural Do and Do Nots and some as well — which Kirsten managed to botch.

A nipply night in nomad’s land.

By Kirsten Koza

(First published in the book, The Best Women’s Travel Writing, Volume 8: True Stories from Around the World)

“Oh, no, Kirsten!”

My Kyrgyzstani guide’s warning came too late, and stepping in poo had never felt so good. My cycling shoe sank into the dreadful yet luxurious warmth of fresh animal dung. I was chilled to the point where I was actually lingering ankle-deep in feces, by choice.

Yena shone the light of her cell phone, its only feature that was still working, onto the molten mound enveloping the bare skin of my lower leg. The droppings looked like something a brontosaurus might have deposited. A meteorite seared across the night sky, so close that you could actually hear it crackle as it hissed down the vertical gorge to the Chong-Kemin valley.

The point of light from Yena’s phone caught me in the eyes. When I’d first met her, yesterday, after traveling thirty-six hours from Canada, I’d told her that I had two irrational phobias. The first one—fear of the dark—I fabricated as an excuse for not wanting to climb the unlit, steep, winding stairs of an eleventh-century minaret. I wasn’t worried about the lack of lighting; I was being lazy. The second phobia—which I’d added to brighten the mood after she looked disappointed that I didn’t want to go up the tower—was real: I was terrified of meteorites. I was seriously scared of being struck by a shooting star. I’d lie in bed at night imagining them out there in space.

Now here we were on a mountain, in the dark, unable to make it across the pass with our bikes because a fresh rockslide had strewn unstable boulders and scree for several kilometers in every direction, including on the slope directly above us. We’d had to turn back and were descending on foot from an altitude of four thousand oxygen-deficient meters above sea level, as night smothered Chok-Tal Mountain. The blinding dark was being shredded by the Perseid meteor shower—shooting stars so close it seemed I could even smell their trails of smelting iron and sulfur. I snuggled into the poop.

“Yena, why did the old Kyrgyz nomad ask me if I was afraid of wolves?”

“I no know why. Is very strange.”

It was weird. It was the only thing he’d communicated, as we’d left his family’s yurt in the afternoon to head up over the mountain chain. He had a wind-whipped and sun-lashed face, a riding crop, a long white moustache, and a traditional white felt hat that made him look like he was wearing a small yurt on his head.

“I’m not scared of wolves,” I said to Yena as she skidded away down the rocky trail beside her bike.

“I know, you say dis already.” Just a few feet ahead of me, and she was invisible.

Suddenly, she shrieked. A clatter of falling rocks started above us and immediately bounced and slid past on all sides. Stone and shale tumbled over the sheer precipice.

I screamed. I didn’t know what was going on, but screaming felt right.

“A horse!” Yena cried.

“Oh, God. Did it go over the edge?”

“It go off.” My guide was somewhere near the edge of the gorge. I couldn’t see her.

“It went off the edge?” All I could hear were the glacial rapids roaring thousands of meters below.

The light from my twenty-two-year-old guide’s phone darted around the nearby mountainside. There was nothing to see in its beam but rocks balancing on good will.

I was too old for this.

Wait, did I seriously just think that? I was furious with myself for even entertaining such a thought. I was not too old for this. I was forty…something. Mid-forties. I’d been lying about my age, saying I was older than I was, for so long that I’d actually need to do the math to figure out my real age. I had never understood why movie stars claimed to be younger than they were. If you lie up in age, then people are amazed by how good you look. But today’s mistakes were those of a twenty-two-year-old. I’d made such errors in judgment decades ago and there was no excuse for repeating them at forty-five-ish.

We had no water, food, supplies, flashlights, or gear of any kind. Everything we needed was in our support vehicle with our driver, Alexey, and my Kyrgyz cultural guide, Cholpon. Everything that could save our lives was on the other side of this snowy mountain range, a six-hour car ride away—if we had a car. When the sun vanished, the temperature had plunged below freezing, and I was wearing shorts and a t-shirt. I’d suggested turning back hours ago, when I’d begun to suspect that I’d misunderstood the plans for the day; I didn’t want to get caught high in the mountains at night.

“Hello, Alexey, hello….” Yena tried her useless walkie-talkie and her useless cell phone for the hundredth time. I knew she was just putting on a front for me. She was fully aware that there was no cell service here, and the transceiver radios were only good if you had a line of sight with the other person. “Hello…” Static.

There had been a tense fight last night at camp between my guides. Alexey had said—in English, for my benefit—“The lady is tired and she has come from living at sea level. We are too high in elevation. Change tomorrow’s ride. Do a small ride, Yena. Don’t cross the mountains.” I agreed with Alexey. Then the arguing continued in Russian, the common language of the three guides supporting my bike trip across Kyrgyzstan.

I didn’t normally travel with a team of babysitters. I’d hired them all before arriving in Bishkek, back when I assumed I’d have a group of cyclists accompanying me. But it turned out nobody else in the world wanted to come to Kyrgyzstan, mostly because of a recent revolution and government overthrow and killings. I’d even received death wishes from an Arizona prison guard on an online mountain biking forum for daring to invite Westerners to a Muslim country. He’d lusted for guns pointed at my head.

Maybe Yena hadn’t understood Alexey’s English when he said we shouldn’t cross the Celestial Mountains. She spoke Russian and French. I could barely understand a word of her English and none of her French, and I was beginning to think she didn’t understand my English, either. Or perhaps she’d won the argument, and nobody thought to tell me. But when we’d left so late in the day, and when I’d watched her hand two bottles of water back to Alexey, complaining they were too heavy – these two clues had indicated we were doing a shorter, easier ride, and not crossing the mountains. She’d even thrown out our food, at which point I was completely certain we’d just be doing a quick jaunt.

Four hours later, when I was vomiting horse milk, clambering over rockslides, carrying, pushing and dragging my bike continually upward, I realized we were doing the full mountain crossing.

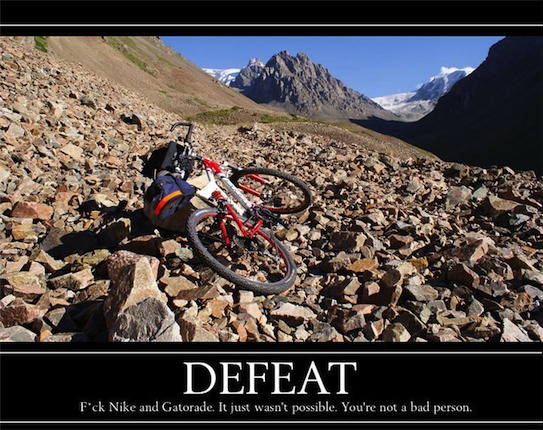

Now, one foot in front of the other, defeated, we were feeling our way back down the mountainside, trembling with cold and muscle fatigue. The incline was so vertical that I was using my bicycle brakes to help slow my pace. I winced as a rock tore the skin off my shin, and again as a shooting star whizzed in front of me. I didn’t make a wish. I wasn’t superstitious. I was just fully freaked out.

The nomads, though—they were superstitious. The Kyrgyz woman who’d served us fermented mare’s milk and bread with jam and clotted cream in her yurt this afternoon had stared at my upside-down bread on the table and shot me a look of horror. I’d also pointed with my foot at her adult son. I was showing him the hardware that attached my shoe to my bike pedal. He’d jumped back and protected his face with his hands. You’d have thought I was going to kick him in the head.

Before traveling to Kyrgyzstan, I’d been sent a warning list on how not to offend or upset the nomads. One of the items on the list said, “Do NOT put your bread upside down on the table,” and the other said, “Do NOT point at anyone with your foot.” I’d cursed the Kyrgyz family with bad luck and brought the devil into their yurt and now I’d startled one of their horses to its death. Maybe they wouldn’t notice. They had lots of horses.

“We leave the trail, now. Here. Here. See light. Is yurt. We go there.” Yena pulled my handlebars to direct me off the trail toward a wavering speck of light in the far distance.

“What? No.” Leaving the trail was insane. Bad things happened when you left the trail. Besides, if we stayed on the trail it would lead us right back to the yurt we were at today. Unless the light was coming from the first yurt we’d stopped at earlier in the day, not the second one.

At the first yurt, a nomad woman had made cheese balls with her bare hands, and I could see her dirty handprints in the sour cheese. My stomach turned at the thought of putting it in my mouth. I pretended to enjoy my golf balls of cheese but palmed them into my pocket, intending to drop them in the outdoor toilet. But when I went to the squat latrine, I realized my cheese balls would be visible to anyone who looked in the shallow hole, so instead I feigned washing my hands in the stream and ditched the cheese there. They instantly sank to the bottom and stayed. The nomads had probably found my cheese after I’d left. They’d know it was my cheese. I didn’t want to go to the first yurt, but then I’d insulted the nomads at the second yurt as well. Plus, there was the issue of the horse.

At the first yurt, a nomad woman had made cheese balls with her bare hands, and I could see her dirty handprints in the sour cheese. My stomach turned at the thought of putting it in my mouth. I pretended to enjoy my golf balls of cheese but palmed them into my pocket, intending to drop them in the outdoor toilet. But when I went to the squat latrine, I realized my cheese balls would be visible to anyone who looked in the shallow hole, so instead I feigned washing my hands in the stream and ditched the cheese there. They instantly sank to the bottom and stayed. The nomads had probably found my cheese after I’d left. They’d know it was my cheese. I didn’t want to go to the first yurt, but then I’d insulted the nomads at the second yurt as well. Plus, there was the issue of the horse.

Following Yena, I stepped off the trail onto an impossible incline of slick wet grass. I turned my bike wheel sideways, as not even the brakes helped stop the downward slide. My front tire suddenly plunged straight down and stopped.

“What’s that?”

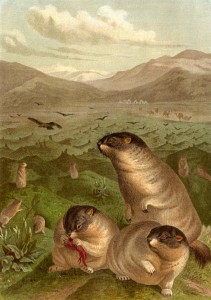

Yena shone her cellphone light. It was a marmot hole. She cast her light over the slope. Between where we stood and the far-off flicker from the yurt was a minefield of marmot holes, all just several feet apart. Before leaving for Kyrgyzstan I’d learned that the marmot was the second deadliest creature known to man, but that was because the marmot carried the flea responsible for the Black Death, or Bubonic Plague—not because their holes were waiting to trap and snap your leg bones like twigs.

Yena shone her cellphone light. It was a marmot hole. She cast her light over the slope. Between where we stood and the far-off flicker from the yurt was a minefield of marmot holes, all just several feet apart. Before leaving for Kyrgyzstan I’d learned that the marmot was the second deadliest creature known to man, but that was because the marmot carried the flea responsible for the Black Death, or Bubonic Plague—not because their holes were waiting to trap and snap your leg bones like twigs.

Using my bike like a senior citizen’s walker, I inched my way down the hill as slowly as possible. It was still too fast. A compound fracture out here would mean certain death. I wasn’t going to die at the hands of Muslims, as the Arizona prison guard had been desperate to prove—I was going to die by marmot.

Just then I became aware of motion, black moving against black, and far too large to be a marmot.

“Yena, what’s that? There’s something out there. No, not something, lots of things.”

We were being surrounded. Large shapes were closing in on us.

“I no know,” Yena whispered.

“Oh, it’s just cows,” I said, relieved.

Except that right then, we heard a deep, guttural, angry growl above us on the mountain. A T-Rex-sized beast was roaring and approaching fast.

“Bull,” Yena cried out in dismay.

The bull circled. I couldn’t see it, but I could hear its hefty hooves impact the soil. It started to paw. It was going to charge. Yena and I made a barricade with our bikes. I heard myself panting—tight, short, breaths that sounded exactly like The Blair Witch Project whimper puffing. People really did make that silly noise. I couldn’t stop doing it. The Minotaur was bearing down on us. We’d be gored.

In a split second, the bull rounded our makeshift bicycle-fence. We were now on the same side of the bikes as him. Yena fumbled with her phone and the weak ray hit the bull’s eye. He charged. We scrambled around our bikes and held them in front of us, sidestepping with them, our bikes locked together in a panicked tangle of handlebars and spokes. I closed my eyes, bracing for impact. He thundered past and around us again. We were an awkward, gasping, four-legged matador.

“Call the nomads to help us,” I begged Yena.

She cried out in Russian, shouting her pleas toward the swinging lantern that marked the safety of the nearby yurt. Then all of a sudden, Yena let go of her bike and ran at the animal—all eighty pounds of her, shrieking threats as she waved her arms over her head and hurtled toward the horned mass of muscle.

I heard men’s voices to my right, speaking in Kyrgyz.

“Help us,” I whinnied.

Where were they? I was still making that pathetic whimpering-huffing noise.

A shepherd whistled a command. A lantern was lit. Dogs. Dogs and nomad men. Muslims. Muslims with guns. I was so happy to see Muslims with guns.

We were ushered into the family yurt. It was the second yurt.

“Kumis?” The mother offered me mare’s milk that had been fermented in a smoked goat’s stomach, again. I’d been up-chucking her kumis all day. Even in my dehydrated state, there would be no swallowing horse milk; the alcohol content was too low to be worth the risk.

I declined politely as Yena spun our adventure to the nomad woman who poured me the traditional half-full cup of tea, which I drank in one gulp. This happened ten times in a row. I wished she’d just pour me a full cup of tea. I wasn’t superstitious.

Her eldest son, whom I’d pointed my foot at earlier, eyed me from under his pile of colorful quilts. It was midnight, and the family lay on the floor, shoulder to shoulder. Where would we sleep? I wasn’t entirely comfortable wedging myself between the nomads on the ground; maybe I could spend the night huddled with the manure-burning stove and the teapot.

“I tell her about rock slide,” Yena said. “I tell her we cannot cross the pass and she say she know this. The same thing happened with Germans on bikes. They come down the mountain last night and sleep here.”

The nomad woman smiled at me with her gold teeth.

“Why didn’t she tell us that this afternoon?” I asked.

“I know. I no know. Is strange,” Yena replied. “We go now. They make bed for us in barn yurt.”

I was so thirsty. I hadn’t had nearly enough half-cups of tea, and as I followed several nomads back out into the freezing night, to the “barn yurt,” I was shaking with the beginning stages of hypothermia. My teeth rattled in my skull. Yena wrapped her icy, spindly arms around me. I don’t like being touched, but I could feel the warmth from her heart on my back, so I didn’t pull away. We shook together as nomads kicked the dogs out of the barn yurt and moved saddles, boots, and riding tack.

“I d-d-don’t mind d-dogs,” I chattered. The dogs ran off into the darkness in a barking frenzy, chasing something unseen.

Yena was handed a lantern, and we stepped into the yurt. I took off my poopy shoes—not that it mattered in the barn, but the nomads were superstitious about shoes—and one tipped over on its side. That was bad luck, too. Now I’d brought bad luck to the barn, as well. I quickly righted my offensive cycling shoe, but not before it was noted by the old man.

On the ground was a mat for us to share. Yena snuffed the lantern, and we crawled under the mountain of handmade blankets on the felt mat and spooned for warmth, feet of course pointed to the flap of the door, for luck. I heard the flap move, and then something else.

“Something is in the tent with us,” I whispered.

“No,” Yena answered.

Something sat down. “Maybe a dog came back,” I suggested.

The dogs responded by barking maniacally in the distance.

“Yes, something is in here,” Yena agreed.

We heard scratching. “Dog,” she sighed.

I suddenly had the feeling that it wasn’t a dog. It was the wolf. But I wasn’t afraid of wolves, I told myself.

Then I coughed. It was a horrible racking cough. Yena rubbed my chest.

No, she was rubbing my boobs. Yena was rubbing my breasts.

O.K., this was worse than wedging in with the family. Did she think I was paying for this service along with her guiding skills? It was beyond awkward.

“Yena,” I coughed, “I’m not scared of shooting stars anymore.” I barked painfully.

“Dis is good.”

“Yeah, now I’m scared of pulmonary edema.” I could feel my lungs filling with fluid. I choked on mucus. Yena rubbed my boobs again.

Day one was over—I hoped. But there were three more weeks to go.

________

Kirsten Koza is an adventure writer, speaker, and the author of Lost in Moscow. Her articles and photographs have been featured around the world in books, newspapers and travel magazines. Kirsten has mountain biked (badly) across twenty countries, was rewarded with a ham for the first mountain bike ascent up Romania’s Mt. Cocora, has driven the intercept vehicle tornado chasing for 19,900 kilometers, kayaked inches from alligators, was held at gunpoint in Honduras for twelve hours, was tattooed by a Rapa Nui tafunga, and has put testicles and penis and many other unusual food items in her mouth. To see pictures and read more about Kirsten’s misadventures visit www.kirstenkoza.com

*I have spelled Elena, Yena, throughout, as that was how I was instructed by her to pronounce her name. Alexey pronounced it Lena and Cholpon said it like Elena.

T-Rex added with Efexio.

This story was first published by Travelers’ Tales, in the 8th volume of The Best Women’s Travel Writing, a series of anthologies edited by Lavinia Spalding. (Click here to see the book on Amazon.)

(My Kyrgyzstan story and photos were first published in TheBlot Magazine, Wall St., New York, in 2014. The magazine’s owner–a Wall St. billionaire–is currently in serious hot water with the FBI. That’s another story. I had an out-of-this-world trip in Central Asia thanks to Travel Experts.)

(My Kyrgyzstan story and photos were first published in TheBlot Magazine, Wall St., New York, in 2014. The magazine’s owner–a Wall St. billionaire–is currently in serious hot water with the FBI. That’s another story. I had an out-of-this-world trip in Central Asia thanks to Travel Experts.)Hop on the Magic Carpet: Visiting Kyrgyzstan is like taking a magic carpet ride back in time to when Marco Polo’s caravans traveled the Silk Road and met Kublai Khan. The Kyrgyz Republic (a former Soviet Republic) exists mostly within the Celestial Mountains (the Tien Shan mountain system). It borders China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. This is not Kar-bomba-stan, so don’t let the “stan” scare you from having a cultural adventure of a lifetime in nomads’ land.

Vodka Guzzling Muslims?: Most of the Kyrgyz people are Muslim, but their beliefs are mixed with shamanism and also atheism which was enforced by the Soviets. The women aren’t veiled and are educated, vodka is enjoyed by many (mostly men, though) and going to a mosque is occasional for most.

Bride Kidnapping Saves on Wedding Bills: At the National Horse Games held in Kyzyl-Oi, Janarbek (a young man from the Sayak tribe) approached my translator Janarkul and asked her if she’d compete in the Capture the Girl competition (also known as “kiss the girl”) because they were short a competitor. The game smacks me in the face with the real-life tradition of bride kidnapping which, although made illegal in 1991, still happens in Kyrgyzstan, but not to westerners. Sergey Gluhoverov and Cholpon Soodaeva, at Travel Experts, told me that Kyrgyz nomad men want demure women who are skilled at making fermented horse milk and felt. Janarkul tentatively asked me if I minded if she competed in the games — of course I didn’t mind.

Tribe Pride: Janarkul is from the clan Taz and the tribe Sarbagysh. She can draw her family tree (nomadic clans) back to around 1276 by memory, and then she can connect her tribe to the original Kyrgyz tribes. She told me that most Kyrgyz can do this. Like Janarbek, she is from a small village of just four clans. She’s comfortable in the saddle, but riding in the games is a bit like being asked to compete in the Olympics when you haven’t been training. Jana has spent the last five years away at school where she is a fully granted student at the Turkish university in Bishkek.

Punch the Boy: Janarkul didn’t speak Turkish before attending the university. She speaks Kyrgyz, Russian and English and had to learn Turkish in her first year. The determined 20 year old told me before the competition that she was not going to be captured and was going to try to leave Janarbek kissing the air, however, she intended to catch him in the second part of the event — “punch the boy.” Her efforts left her bruised and sore, with a prize of cash and chocolate bars — and also with an invitation to compete again next year.

Fermented Horse Milk: The still-popular traditional drink of the Kyrgyz people is kumis, fermented mare’s milk. It’s drunk in such vast quantities that it could be considered a staple. Although kumis is often compared to kefir, unlike kefir, kumis has a mild alcoholic content which is due to the higher level of sugar in a horse’s milk. The milk is always fermented since, when fresh, it is reputed to be a laxative. People unused to even the fermented version might find adverse effects and many vomit after trying kumis, so you might want to rein back the temptation to chug it. The first and last time I sampled kumis, it had been fermented in a smoked goat’s stomach. The alcohol content of kumis is not high enough for me to make the after-effects worth acquiring a taste for the pony cocktail.

Galloping Gourmet: Nomads prize their horses above anything else, thus, it might seem unusual that the Kyrgyz also consume the flesh of horses. When my translator first showed me the pictured sausages and said they were horse, I thought I was looking at stallion manhood, but they’re horse-fat and horse-meat sausages. Horses are only killed for feasts for important events such as funerals. At a whopping 800 Som for 2.2 pounds (around $15 U.S.), horse sausages are a special occasion sausage.

No Fast Food Here — We’re Kyrgyz: There aren’t any western fast food chains in Kyrgyzstan yet, but modernization might be just around the corner as in 2015 Russia wants Kyrgyzstan to join its Customs Union (Putin’s version of the EU — though some joke that it is an attempt by Putin to put the Soviet Union back together again).

Eat, Prey, Kill: Artsan Sagymbaev (of the tribe Bugu and the clan Jalgap) keeps his family’s tradition alive. He is a 6th generation eagle hunter in Bokonbaeva (a village of eagle hunters) on the shores of the salt lake Issyk-Kul. An “eagle hunter” means hunting with an eagle, not hunting for eagles. Artsan proudly showed me his eagle Saryeiji’s kill from the previous winter; his 8-year-old female bird had caught an 88-pound bobcat.

Got Your Goat: Kok-boru (which means “grey wolf”) is a rough horse game which originated as a nomad hunting exercise. To the untrained eye, it looks like a scrum of rugby players wrestling on horseback between two goals, but the players all have positions and jobs, such as guarding the pin (the goal). Good players have national celebrity status and remarkable horse skills. The players need to be able to pick the “ball” (a dead goat) off the ground while in their saddles, ride with the cumbersome and heavy game-piece and wrestle it from other players. A goal is scored when the goat is stuffed into the pin, a small hole inside a larger ring in the opposing team’s end zone.

Tender Vittle: As I waited for the game of Kok-boru to begin, an announcement was made that it would be just five minutes longer as the goat was being “prepared.” I knew what this meant. Billy was being slaughtered, decapitated and having length chopped off his legs. The animal was brought to the playing field still bleeding and, although newly dead, it looked like it was still twitching with life. Animal-rights activists have complained about this; however, Kyrgyz people wouldn’t waste a goat. After the game, the now-tenderized goat is eaten. The goats are donated to a family in a nearby community who are known for their outstanding service, or to a family that has an upcoming wedding to celebrate. After the game I attended, the goat was awarded to the captain of the team. The players were on a rotating roster to donate a goat for each game.

No Matter What the Locals Say, Vodka Does Not Cure Altitude Sickness: The average elevation in Kyrgyzstan is approximately 9.022 feet above sea level, and its tallest peak is 24,406 feet. The Kyrgyz nomads move their livestock up and down in elevation with the seasons. The landscapes vary from jagged peaks to colorful red, white and blue-striped badlands, mineral-rich mountains (whose minerals cause rivers and lakes to take on exotic hues), alpine meadows, impressive glaciers and pine forests. There are less than 6 million people in Kyrgyzstan, and more than 70 percent of the population is Kyrgyz, around 14 percent are Uzbek and 10 percent are Russian.

Nomad Tax Evasion: Yurts are collapsible, portable homes made of sheep’s felt layered over a wooden frame. While people often assume a nomadic life means the freedom of moving wherever one chooses, that’s not actually the case. The nomads are territorial, and the same families erect their yurts on the same land that their forbearers did for many generations. They don’t own the land, the government does now. While at Lake Song-Kol where my translator Janarkul’s grandfather had his yurt, Jana informed me that the government taxes the nomads by placing a tax per head on their livestock. I asked her if the nomads ever hid animals so as to avoid paying tax, and she said, “No.” I was suspicious of her response, so I encouraged her by saying, “That’s what I’d do if I were a nomad. I’d go higher into the mountains with some of my herd and would hide them.” Jana laughed, saying, “Yes, that’s what they do. We know what day the government is going to be sending the tax-people to count the animals, so the shepherds hide some of the animals higher in the mountains.”

Holy Rumpelstiltskin: There is a still practiced tradition today among the Kyrgyz people in which the eldest son’s first-born son is taken by the grandparents to be raised like their own. My translator’s parents “took” her brother’s first-born from her sister-in-law.

Don’t Judge a Book by its Cover: A Kyrgyz woman might be dressed traditionally or be known for her kumis or carpet making or she might have received an award for giving birth to seven children or spend a lot of time hand-rolling yogurt cheese balls, but at the same time, she might have a degree in economics and a job with the government.

Nomads’ Land No More: The Soviets forced the Kyrgyz nomads into settlements. The nomads didn’t go willingly, and it was a violent time in history. By law, all Kyrgyz children had to go to school, which is still true today. The forced settlement forever changed the way of life of the nomads. Now, many live in villages in valleys and basins during the winter months and then in the summer return to their nomadic pastures with their livestock.

TRAVEL TIPS:

Getting There: I used FlightFox to book my plane tickets to Kyrgyzstan. A team of real people actually search for the best deals, taking into consideration your personal wishes, whether that be cheapest price, short layovers or most direct route. The cheapest flight was on Aeroflot, which flies direct from North America to Moscow, then to Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia. They no longer serve vodka in economy on these flights, but you do get one glass of wine. There are also flights to Bishkek on Turkish Airlines.

Traveling in Kyrgyzstan: Travel Experts in Kyrgyzstan is a company that understands what being a consummate host is all about. They can arrange cultural tours, horse tours, mountain biking, dirt biking, four-wheel drive, skiing, trekking and much more. You can rent cars or 4×4’s from luxury models to economy. Their drivers are excellent should you prefer not to self-drive. Travel Experts can book you into the best hotels in Bishkek, most remote yurts or village guesthouses. They’re award-winning and have well-trained guides.

Accommodation: CBT (Community Based Tourism Association) guesthouses are rated in edelweisses instead of stars with the highest being four flowers. The highest-rated guesthouse in Kyrgyzstan is three edelweisses. This means it has indoor toilet facilities, is clean and is environmentally responsible. The CBT checks the guesthouses every spring and gives them their ratings.

THIS PAST EXPEDITION IS COMPLETED – STAY TUNED FOR NEW KYRGYZSTAN EXPEDITION

Writers’ Expeditions: Itinerary, Prices and Details (Aug 14-25, 2014)

Kyrgyzstan Silk Road and Off Road: a four-wheel-drive adventure of a lifetime through remote landscapes to capture the nomad horse competitions and eagle hunting festival (that’s hunting with eagles not for eagles). In three 4x4s (driven by local award winning tour operator, Travel Experts of Kyrgyzstan) our small group will cross the Tian Shan mountains often by dirt track on an expedition hosted by professional photographer Dave Sloan of Sloan Shoots (with more than 30 years of experience that you’ve seen in most magazines and even in huge corporate ad campaigns such as IKEA and other household names, banks, museum posters, and gigantic images on the sides of 18-wheelers hauling your favourite food right now); and also hosted by author, adventure travel writer, journalist, and humourist, Kirsten Koza.

Small Group (8): This journey is designed around exciting experiences and cultural curiosities. It’s for anyone with a camera or device that takes photos; no matter your photography skill level, we’ll cater shooting tips to suit your needs and wishes.

Kyrgyzstan is in Central Asia and borders China, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. It was formerly part of the USSR. The people speak Kyrgyz and/or Russian. Visiting Kyrgyzstan is like taking a magic carpet ride back in time to see Genghis Khan or dine with Marco Polo’s caravan. You’ll definitely know you’re no longer in Kansas when in Kyrgyzstan.

Itinerary, Prices, and Highlights About Your Expedition Hosts:

14.08, Day 1: Bishkek city tour

Your guides will pick you up at Manas International Airport and accompany you to the capital city of Kyrgyzstan, a 30-minute drive from the airport. We’ll explore the city of Bishkek which is thought to get its

name from the Kyrgyz word for “churn,” the device used to make the national drink, fermented horse milk. Bishkek is a city of contrasts; glorious marble facades, trees sprouting through dangerous pavement cracks, domed roofs with a backdrop of the Ala-Too mountains, ugly Soviet-style apartment blocks and the odd statue of Lenin, plus a colourful bustling Asian bazaar and market. Traditional dinner will be served at 7 p.m and then back to The Grand Hotel (with free wi-fi and air conditioning) where we can charge our batteries (metaphorically as well).

name from the Kyrgyz word for “churn,” the device used to make the national drink, fermented horse milk. Bishkek is a city of contrasts; glorious marble facades, trees sprouting through dangerous pavement cracks, domed roofs with a backdrop of the Ala-Too mountains, ugly Soviet-style apartment blocks and the odd statue of Lenin, plus a colourful bustling Asian bazaar and market. Traditional dinner will be served at 7 p.m and then back to The Grand Hotel (with free wi-fi and air conditioning) where we can charge our batteries (metaphorically as well).

In the morning we’ll start our journey to the second largest alpine lake in the world (Peru’s Lake Titicaca being the largest). On route we’ll visit Burana Tower (an 11th century minaret) the remnants of a mosque from the medieval city of Balasagun. The minaret is surrounded by intriguing 6-10th century Balbals (Turkik ancestors, stone warriors that look like mini versions of Easter Island’s mysterious moai). After a traditional lunch, we’ll continue on our way to Issyk Kul lake (stopping when we see something worth capturing). Although surrounded by snow capped mountains, salty Issyk Kul never freezes. We’ll swim at a wild beach before heading to our guesthouse at Tamga village. A “tamga” (from Mongolian language) was a stamp or seal used by an individual clan of nomadic peoples. Dinner will be served at 7 p.m.

16.08, Day 3: Tamga – Eagle Hunting Festival!

Today will be a photographer’s wet dream. We’ll sample Kyrgyz cuisine, experience national folklore, and we’ll get to witness a show of  eagle hunting. The eagles are a lifetime commitment; a man bonds to bird and bird to man. The skill is passed down for many generations. The hunt is executed with the help of taigans (Kyrgyzskaya Borzaya Taigan dogs), a special breed of sighthounds (used since ancient times) trained to hunt wolves, foxes, marmots, badgers, hares; animals used for both sustenance, clothing and the fur trade.

eagle hunting. The eagles are a lifetime commitment; a man bonds to bird and bird to man. The skill is passed down for many generations. The hunt is executed with the help of taigans (Kyrgyzskaya Borzaya Taigan dogs), a special breed of sighthounds (used since ancient times) trained to hunt wolves, foxes, marmots, badgers, hares; animals used for both sustenance, clothing and the fur trade.

17.08, Day 4: Tamga – Tosor – Naryn

After breakfast we’ll begin the back country, off-road & dirt track portion of our 4-wheeling adventure into the wilds of Kyrgyzstan. We’ll drive up over Tosor pass at more than 3,000 metres above sea level. That’s 600 metres higher than Machu Picchu. If you’re worried about altitude sickness talk to your doctor or travel health clinic about getting a  prescription of Diamox (acetazolamide). Kirsten finds it works well and enjoys the pleasing tingly fingers and tingly toes side effects. The day promises breathtaking views. It will be possible to meet and photograph nomadic families. If you’re offered fermented horse milk, it’s probably best to politely decline or pretend to sip unless you enjoy vomiting. Night will be spent in a Khan Tengri Hotel in Naryn (2,044 metres) a town situated on either side of the river gorge.

prescription of Diamox (acetazolamide). Kirsten finds it works well and enjoys the pleasing tingly fingers and tingly toes side effects. The day promises breathtaking views. It will be possible to meet and photograph nomadic families. If you’re offered fermented horse milk, it’s probably best to politely decline or pretend to sip unless you enjoy vomiting. Night will be spent in a Khan Tengri Hotel in Naryn (2,044 metres) a town situated on either side of the river gorge.

18.08, Day 5: Naryn – Tash Rabat

18.08, Day 5: Naryn – Tash Rabat

After breakfast we journey to the Tash Rabat Caravanserai (a 14th century stone castle) on the spectacular Silk Road; the ancient trade route used by merchants, soldiers and monks, connecting West and East. Tash Rabat is not far from the Chinese border and is at the very heart of the Tian Shan Mountains. The castle is built into the inside of a mountain at an elevation of 3200 metres above sea level. There are around 31 rooms in the mountain, some being former cells used to incarcerate thieves. The intimidating stone block walls are 1 metre thick. There will be a traditional dinner again this night but this time the night will be spent in yurts near Tash Rabat Caravanserai. This might be a good night for us to use our collective flashlights to create eerie long exposure images.

19.08, Day 6: Tash Rabat – Son Kul

19.08, Day 6: Tash Rabat – Son Kul

After many half-cups of tea (that’s how they serve it in Kyrgyzstan) we’ll start our drive over rugged terrain to the second largest lake in the country. Son Kul is also the highest alpine lake in Kyrgyzstan, situated at an

altitude of 3013 meters above sea level. Herders of the Naryn region go to the lake every summer to graze their livestock on the fertile pastureland. After our arrival, you will be free to indulge in your surroundings. Dinner and overnight is in the nomadic collapsible dwellings – yurts. They are made of a wooden skeleton, covered with felt. Yurts are usually heated by dung burning stoves and the nomads provide toasty warm, heavy, handmade blankets.

altitude of 3013 meters above sea level. Herders of the Naryn region go to the lake every summer to graze their livestock on the fertile pastureland. After our arrival, you will be free to indulge in your surroundings. Dinner and overnight is in the nomadic collapsible dwellings – yurts. They are made of a wooden skeleton, covered with felt. Yurts are usually heated by dung burning stoves and the nomads provide toasty warm, heavy, handmade blankets.

20.08-21.08, Day 7-8: Son Kul Lake – saddle up for a horse ride

These 2 days will be spent exploring the shores of Son Kul Lake. This is a chance to experience real nomadic life. We’ll also get to take a 3 hour horse ride (but you don’t have to do this) or you can keep your horse for an entire day. We’ll have multiple chances to capture sunrises and sunsets over the scenic lake, dotted with yurts and grazing horses along its pristine shores. And this is a great chance to get acquainted with nomadic people, their traditions, ways of life, and many superstitions. You’ll see women milking horses to make kumis (the fermented mare’s milk) and children who ride so well you’d think they were born on a horse. All nomads are very hospitable. They are not used to seeing many tourists and are  always happy to speak with you. Hospitality is one of the main unwritten laws among nomads. They have a saying: “A guest is sent by God.” So they cannot just let you pass without inviting you to visit with them. Meals and accommodation will be in genuine nomadic dwellings – yurts.

always happy to speak with you. Hospitality is one of the main unwritten laws among nomads. They have a saying: “A guest is sent by God.” So they cannot just let you pass without inviting you to visit with them. Meals and accommodation will be in genuine nomadic dwellings – yurts.

22.08, Day 9: Son Kul – Kyzyl Oi

After making sure you don’t put your bread upside down on the table at breakfast (another superstition that brings bad luck upon the yurt) we will start to make our way to the very remote village of Kyzyl Oi, which means Red Valley. The drive to Kyzyl Oi traverses over one of the most beautiful passes in Kyrgyzstan, right along the top of a mountain. You will have magnificent climbs, thrilling descents, and panoramic vistas. On the way we will drive over Kara Keche pass which is 3364 meters high. After driving to the top of the pass there’s a long sweeping descent. Night and dinner will be in a home stay.

23.08, Day 10: Kyzyl Oi, Nomads’ National Horse Games (we’re privileged travellers because these games are for nomads, not tourists)

Today we’ll experience the Nomad’s National Horse Competitions at their annual festival. Nomads come from all over the steppes and mountains of Kyrgyzstan to partake and compete. Beside the horse games you will also get to listen to Folklore perform (music) and taste Kyrgyz cuisine. Below is the description of the main sporting events:

Today we’ll experience the Nomad’s National Horse Competitions at their annual festival. Nomads come from all over the steppes and mountains of Kyrgyzstan to partake and compete. Beside the horse games you will also get to listen to Folklore perform (music) and taste Kyrgyz cuisine. Below is the description of the main sporting events:

- Kyz Kuumai: translates as “Chasing the Girl.” This demonstrates the riding talent of both man and woman. After a head-start is given to the woman a man at full gallop starts to chase after her and tries to reach her and win or steal a kiss. The woman tries her best to escape him so she can reach the finish line and turn back and start chasing after the man in order to whip him all the way to the starting line. It is considered a huge shame for the man to be beaten, the pressure for him to show his superiority is significant. In former times this game was played by young couples in love with each other, so a girl who was on the way to winning would purposely slow down so as not to humiliate her beloved in front of the people.

Tyiyn Engmei: means “Grab the Coin.” Coins are laid upon the ground and a young man has to grab them while galloping on a horse at full speed. This game was played a lot in former times as a way of training for riding in battle. This game taught the young how to be solid on a horse and also helps develop flexibility.

Tyiyn Engmei: means “Grab the Coin.” Coins are laid upon the ground and a young man has to grab them while galloping on a horse at full speed. This game was played a lot in former times as a way of training for riding in battle. This game taught the young how to be solid on a horse and also helps develop flexibility. Er-Enish or Oodarsyh: Two tough shirtless men on horses wrestle. They also cover their bodies with oil to make it more difficult to pull their opponent off the horse. The rules do not allow them to punch the face, kick, bite, or whip. Technically they are just supposed to use their bare hands to pull the other from his mount. The participants demonstrate strength at the same time as skillful management of horses.

Er-Enish or Oodarsyh: Two tough shirtless men on horses wrestle. They also cover their bodies with oil to make it more difficult to pull their opponent off the horse. The rules do not allow them to punch the face, kick, bite, or whip. Technically they are just supposed to use their bare hands to pull the other from his mount. The participants demonstrate strength at the same time as skillful management of horses.

24.08, Day 11: Kyzyl Oi – Bishkek

24.08, Day 11: Kyzyl Oi – Bishkek

After socializing with locals, we’ll start our journey back to Bishkek. The road to the city goes through the southern part of Kyrgyzstan. Once again we’ll encounter impressive mountains and gorges and the panoramic views of Tue Ashuu pass which is more than 3000 meters high. This road is considered to be one of the most beautiful in Kyrgyzstan. There will be many photo stops and opportunities to stretch one’s legs and maybe to buy some mountain pasture honey from a local beekeeper so you can taste the floral scent of Kyrgyzstan’s meadows when you return home. We’ll have dinner and a traditional concert just for us performed by the Kyrgyz band Folklore. The night will be passed at The Grand Hotel again in the capital.

25.08, Day 12: Bishkek – Airport

If you are departing Kyrgyzstan this morning you will be transfered to the airport.

More Details About Your Expedition Hosts, Prices and Inclusions:

Dave Sloan will guide you on a journey (catered to your skill level and goals) to take stunning images, ones that you’ll want to frame when you get home. Anyone interested in writing, whether for personal pleasure, or in expectation of having work published, will have Kirsten Koza there to give feedback and share valuable hard earned tips.

Dave Sloan (www.sloanshoots.com) completed a Bachelor of Applied Arts in photography at Ryerson in 1985 and for 30 years he has been shooting professionally. You’ll have seen his incredible photos in ad campaigns for IKEA, or perhaps the award winning campaign for the Buskers Festival in Toronto, Molson’s beer, Rogers, TD Bank, Royal Ontario Museum, City of Toronto, T.T.C. and more. His food images drive down highways on the sides of President’s Choice trucks (making Canadians drool and buy insurance),and his work decorates bus shelters, is blown into posters, and has been in most magazines. He’s an experienced traveller, outdoorsman, mountain biker and snowboarder.

Your other host is Kirsten Koza a 48 year-old author, adventure travel writer, journalist and humourist. Kirsten made the front page of Kyrgyzstan’s national newspaper for “discovering” Kyrgyzstan for travellers. She mountain biked across Kyrgyzstan and found the perfect guides and ultimate experiences for this expedition and will be happy not to have her bike on this trip. Her stories and images (including ones about Kyrgystan) have been published in books, magazines, and newspapers around the world: The Guardian.uk, Travelers’ Tales anthologies, DreamScapes travel and lifestyle magazine, Central Asia Business & Society magazine, Outpost, Guatemala Times, Iquitos Times, TheBlot (Wall St., New York) and many more.

Your other host is Kirsten Koza a 48 year-old author, adventure travel writer, journalist and humourist. Kirsten made the front page of Kyrgyzstan’s national newspaper for “discovering” Kyrgyzstan for travellers. She mountain biked across Kyrgyzstan and found the perfect guides and ultimate experiences for this expedition and will be happy not to have her bike on this trip. Her stories and images (including ones about Kyrgystan) have been published in books, magazines, and newspapers around the world: The Guardian.uk, Travelers’ Tales anthologies, DreamScapes travel and lifestyle magazine, Central Asia Business & Society magazine, Outpost, Guatemala Times, Iquitos Times, TheBlot (Wall St., New York) and many more.

Meet your support team at Travel Experts in Kyrgyzstan in this dynamic YouTube video which also gives a good feel for the terrain we’ll be encountering on our expedition. Travel Experts have won the distinction of being the best tour operator in Kyrgyzstan two years running.

Prices and Inclusions:

$2600 USD (a $350 deposit reserves your spot. Then the later payments are made to Travel Experts in Kyrgyzstan for the tour portion of your trip and to Writers’ Expeditions for the workshop.)

Service includes:

- All meals

- Accommodation

- Photography & Writing workshops (on the move, on location – not in classroom setting – these are optional but are fabulously fun and skill building)

- English speaking guide

- 3 drivers

- Eagle hunting show

- Horse games

- Folklore music show in Bishkek

- Transport 3 4×4 Mitsubishi Delica vans

- Horse riding at Son Kul for 3 hours

- Mineral water during the tour

Service does not include:

- Single rooms: $100 supplement for entire trip (during the nights in the yurts, however, we have to sleep 4 or 5 to a yurt – nomad style)

- Early check-in upon arrival: $40

- Single early check-in $70

- airfare

- extra horse hire (keep your horse at Son Kul) for the full day for an additional $15

- Travel insurance (must be obtained)

- Visa and visa support (Canadians no longer need a visa for Kyrgystan)

- alcohol (vodka is cheap like borscht in Kyrgyzstan)

Can’t come in August–then perhaps you’d be interested in spending Halloween in Transylvania, Romania?

Contact Kirsten: info@kirstenkoza.com or on Facebook at the Writers’ Expeditions page. She responds quickly so try the contact form on her website if you don’t hear back within 24 hours.

August 14-25, 2014, in three 4x4s our small group will cross Kyrgyzstan’s Tian Shan mountains, on a cultural and photography adventure, to capture the nomads’ horse games and eagle hunting competitions.

Kyrgyzstan borders, China, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. It was formerly part of the USSR.

I biked for almost a month (when my bike wasn’t hitching rides on horses) across Kyrgyzstan researching this trip. I have found the best guides, and Kyrgyz tour operator to support our expedition (not on bikes) through nomads’ land and along the Silk Road.

(Prices and full details will be available now!)